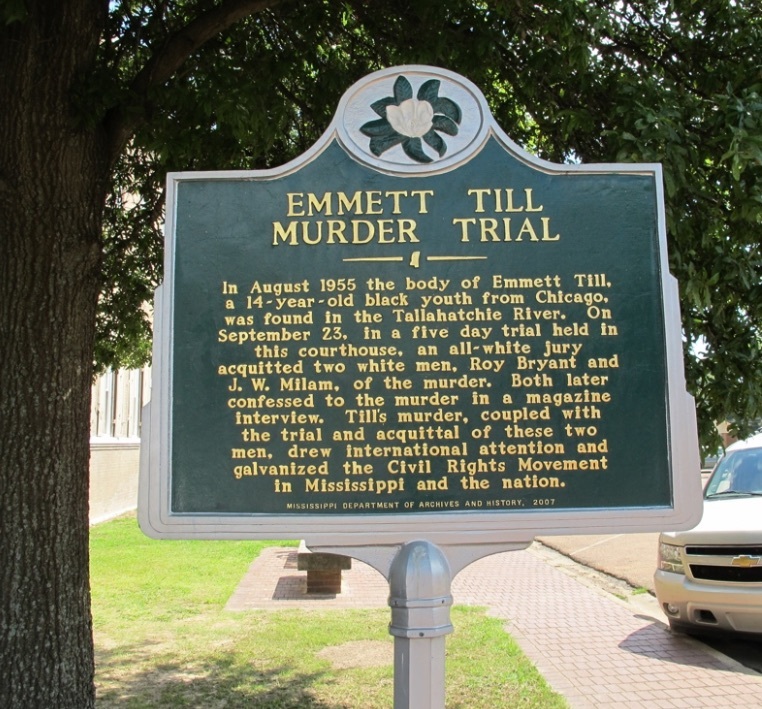

For nearly 50 years, the murder of Emmett Till was not commemorated in Tallahatchie County. Even the courthouse itself hid the story. Only recently has the second district Tallahatchie County Courthouse been used to tell Till's story.

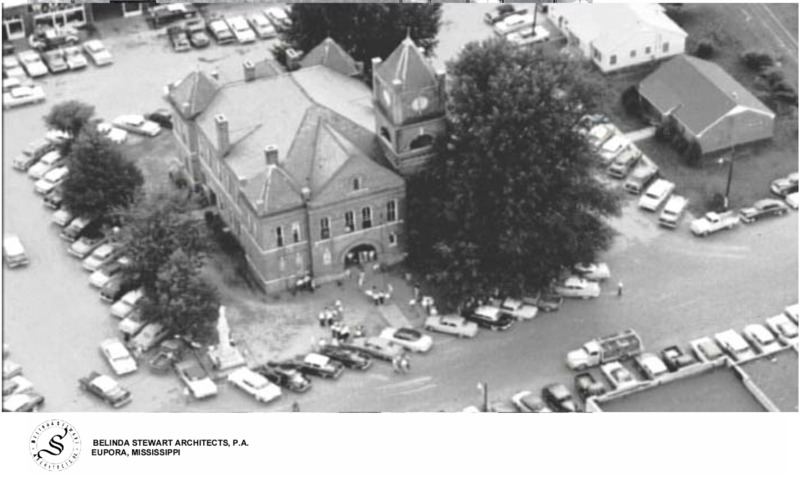

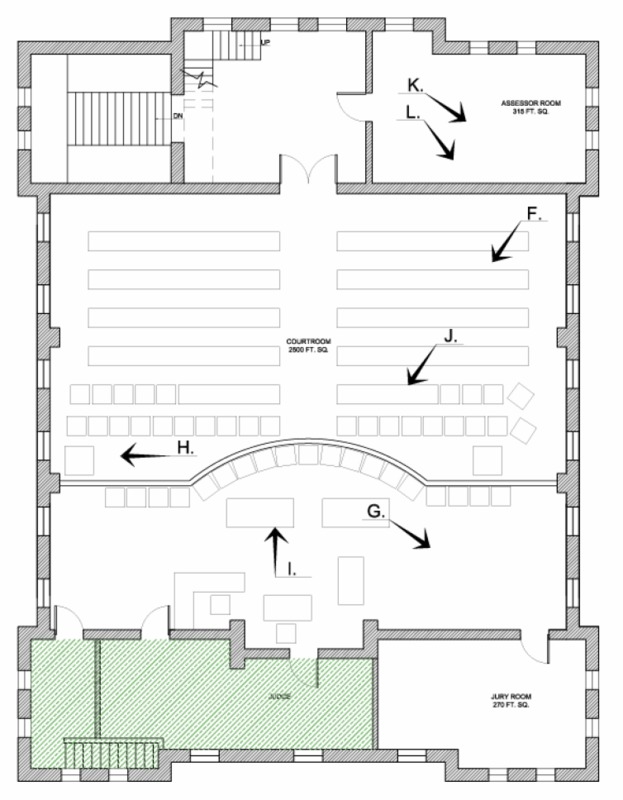

On September 19, 1955, at 9:25 am, the trial of J. W. Milam and Roy Bryant for the murder of Emmett Till opened in this courthouse. It was a sensational, five-day trial. For the first time in history, the Northern press descended on a Mississippi trial. To this day, locals recall the spectacle that was the Till trial: the microphones, the cameras, the reporters, and the stifling heat of the second-floor courtroom. With approximately 400 people crowded into the small space (sitting in aisles and hanging out of windows), temperatures inside exceeded ninety degrees. For all these reasons, celebrated journalist David Halberstam, who attended the trial as a reporter for a West Point, MS newspaper, called the trial “the first great media event of the civil rights movement.”

The trial lasted a scant five days. It would have been even shorter, had the black press not managed to secure an extended recess on the second day of the trial. Baltimore Afro-American reporter James Hicks, Medgar Evers, and Mound Bayou’s Dr. T. R. M. Howard rounded up five witnesses that claimed (correctly) that Till was beaten (and possibly killed) by J. W. Milam and others in a barn outside of Drew, MS. Drew was 20 miles southwest in Sunflower County, and, if the witnesses were correct, the trial would have to be moved to the neighboring county. Judge Curtis Swango called a recess to investigate the possibility. In the end, the witnesses were not believed and the trial was not moved.

On Friday, September 23, the all-white jury took only 67 minutes to deliberate before returning a verdict of not guilty. It was widely reported that the only reason it took them as long as it did was that they drank some Cokes in order to make it appear as if they were struggling with the decision.

The Cokes notwithstanding, the jury did not struggle to reach a verdict. They believed (or at least they said they did) the testimony of Sheriff H. C. Strider, Harry D. Malone, and Dr. L. B. Otken—all of whom argued that the body could not be positively identified as Emmett Till. The body was so badly decomposed by the time it was retrieved from the Tallahatchie River, these men argued, that the race of the body could not be determined. And, if the race of the body could not be determined, there was no way to verify that the body was Emmett Till. Thus were the murderers acquitted.

The testimonies of these men are deeply suspect. Malone never saw the body (although he claimed he did), and Strider changed his mind in dramatic fashion. A month earlier, when the Sheriff pulled Till’s body from the water, he marked the death certificate “colored” and sent the body to Chester Miller’s Century Burial Funeral Home—the black funeral home in Greenwood. His later suggestion, under oath, that the body was so decomposed that its race could not be determined was nothing more than a lie to secure an acquittal.

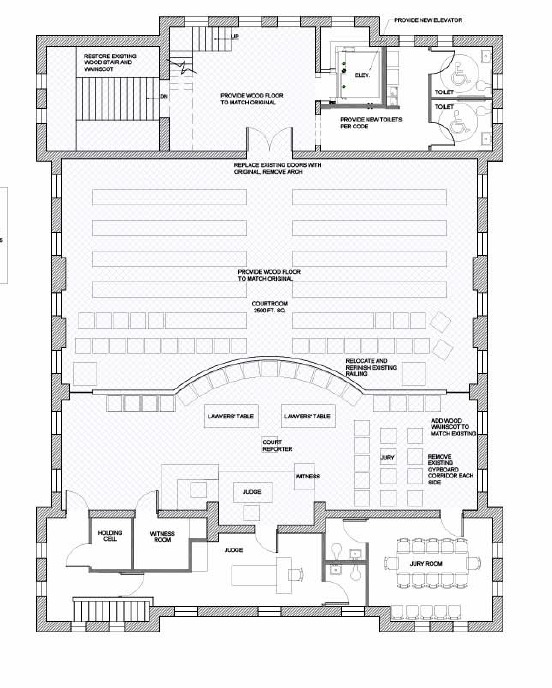

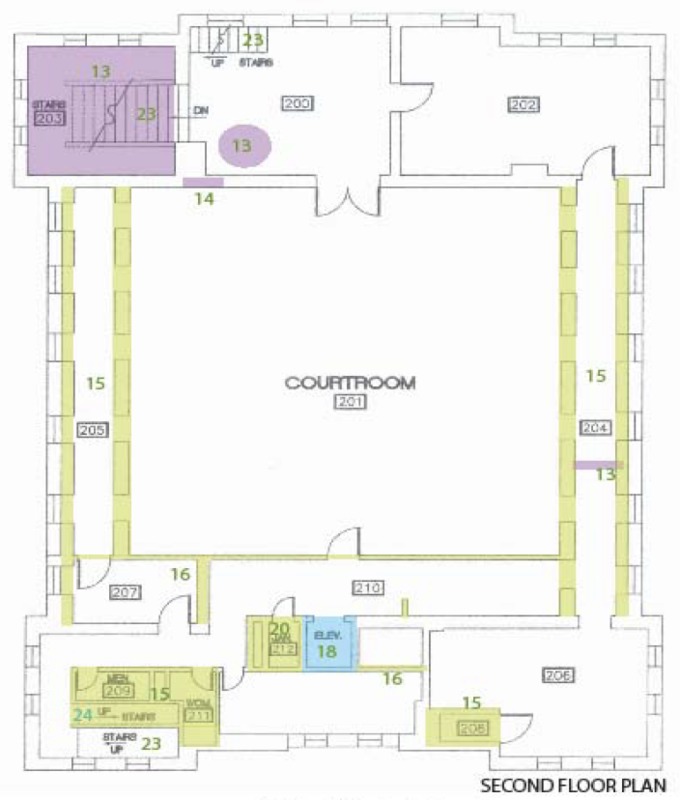

On July 1, 1972, the Tallahatchie County Board of Supervisors announced that the Courthouse in Sumner would be renovated by Yazoo City architect Jack DeCell. In the name of modernization, and at a cost of $235,000, the chairs were replaced with pews, the sash windows were replaced with solid glass, interior walls were added to the courtroom to shrink the space by over 800 square feet, and the courtroom was painted purple. The renovations were so dramatic that some locals believe the DeCell renovation was intended to bury all memory of Till’s murder. Those who believe this are quick to note that it was during the DeCell renovation that the cotton gin fan that once anchored Till’s body was lost.

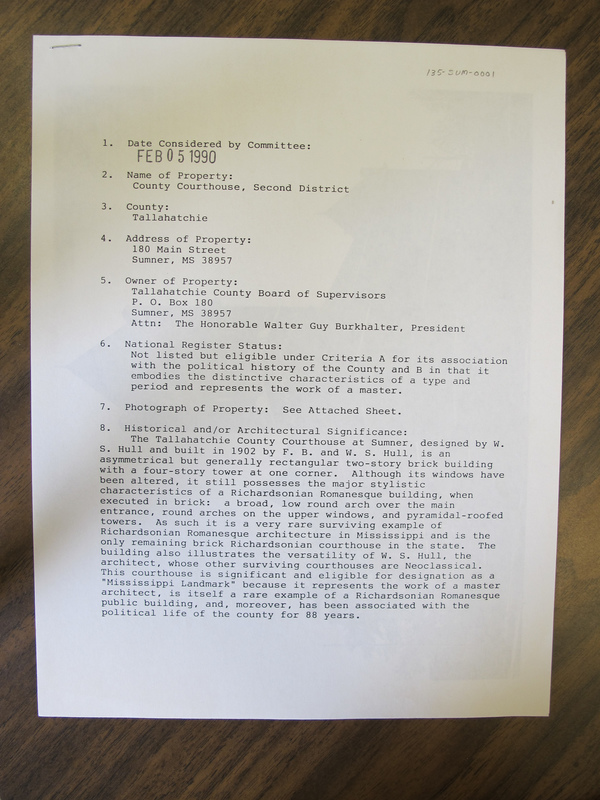

In 1990, the Sumner courthouse was listed on the state register of historic places. Curiously, the historic places nomination makes no mention of the Till murder. The courthouse is nominated only for architectural reasons. The courthouse, the state claimed, is one of a very few remaining examples of Richardsonian Romanesque architecture. For some, this focus on architecture and the complete silence on the famous trial seemed like yet another attempt to forget Till’s murder.

Beginning in 2005, the Emmett Till Memorial Commission set out to undo the work of DeCell and the historical nomination. By renovating the courthouse to its 1955 condition, the Commission shifted the primary narrative of the courthouse. It was no longer about architecture; it was about race, memory, and justice. In this spirit, the Commission organized a formal apology to the Till family from the county in 2007.

In 2015, the space reopened, both as an operating courthouse and a living memorial to the Till murder. The renovation was done by Belinda Stewart Architects of Eupora.

Video

Images

Documents

| Name | Info | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| National Register Nomination Form, Second District Tallahatchie County Courthouse | pdf / 3.02 MB | Download |

| Tallahatchie Civil Rights Driving Tour Brochure, 2007 | pdf / 854.33 kB | Download |

| As We See It... | pdf / 394.73 kB | Download |