Originally the Glendora Cotton Gin, Glendora Mayor Johnny B. Thomas transformed this building into one of the earliest Till museums in the world: the Emmett Till Historic Intrepid Center (the ETHIC museum).

The story told in the ETHIC museum is unique on two counts.

First, while virtually every 20th-century history of Till’s murder suggests that the murderers dropped the body in the Tallahatchie River, the commemorative work in Glendora suggests that Till was dropped into a tributary known as the Black Bayou from a bridge on the south side of Glendora. According to this account, the bayou then carried Till’s body for 3 miles to the Tallahatchie River, where it was recovered near Graball Landing.

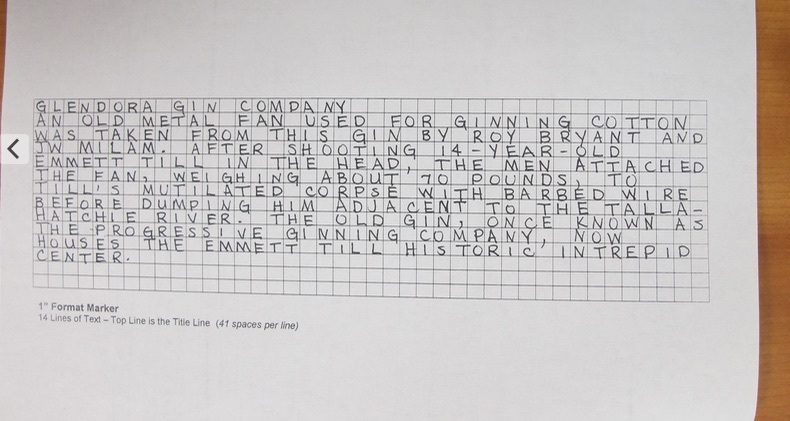

Second, while no historian has been able to claim with certainty where the murderers obtained the fan they used to weigh down Till’s corpse, the Glendora museum claims that the fan was stolen from this site, the Glendora Cotton Gin, presumably by Elmer Kimbrell, a gin employee and the next-door neighbor of confessed murderer J.W. Milam.

While these variations on the finer points of Till’s story are contested, to Glendora residents they are matters so weighty that it seems as if the very future of the town hinges on where Till’s body was dropped in the water and what fan weighed it down.

In 2010, the Mississippi Development Authority sent a team of economic development experts to Glendora. Their charge was to devise a plan to rescue the town from poverty — a tall order. Glendora is marked by breathtaking poverty with a median household income 70% below the state average.

The team struggled to find solutions. Aside from the unrealistic suggestion that the town turn the snake-infested land along the bayou into “riverfront property,” their only other proposal was that Glendora capitalize on its connection to the Till murder. More commemoration, they said, would bring tourists; tourism would beget economic development. The viability of this suggestion, of course, turned on a version of Till’s story that maximized the relevance of Glendora.

None of this was news to Glendora Mayor Johnny B. Thomas. Since at least 2005, he had been promoting a Glendora-centric narrative of the murder in which Till’s body was dropped in the Black Bayou tied with a fan from the local gin.

While these are both plausible claims, Thomas’s efforts have been undermined by a consistent antagonist: the Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH).

The MDAH has invested more funds into Till’s commemoration than any other organization. It restored the Tallahatchie County Courthouse, the site of the Till trial, and even invested more than $200,000 in the controversial restoration of Ben Roy’s Service Station in Money.

The agency, however, is not convinced that Till’s body was dropped from the Black Bayou Bridge. Nor does the organization believe that the fan was stolen from the local gin. It has thus rejected every grant application the town has ever submitted. Locals are quick to point out that the MDAH funded the white memorial in Money (despite its implausability) but denied the all-black town of Glendora (despite its plausability).

Mayor Thomas (and the entire town of Glendora) was in a bind. They had one state agency (the MDA) telling them to invest in Till commemoration and a second state agency (the MDAH) blocking their every attempt to do so.

While some people might give up, Mayor Thomas got creative.

By leveraging the poverty of the town, he has obtained grant money from other sources. The work began on Sept. 27, 2005. On that day, the U.S. Department of Agriculture awarded a Community Connect Broadband Grant to Glendora. Funded at $325,405, the grant was intended to bring broadband connectivity to Glendora. Thomas used the grant to both provide broadband and build the first version of the ETHIC museum. In April 2010, he received an IMLS grant to professionalize the museum.

The USDA grant program was intended to alleviate poverty. The Mayor’s ingenuity and creativity was able to bend those dollars to create a much-needed museum.

And yet, questions remain unanswered. Was Emmett Till actually dropped from the Black Bayou Bridge? Was the fan stolen from a local gin? Was Elmer Kimbrell involved?

Perhaps. But it is impossible to separate the truthfulness of these claims from the poverty of the townspeople. Thomas has leveraged the town’s poverty to build a museum, and the museum, in turn, supports Glendora’s plausible-but-unverifiable theories of the murder.

Had Glendora been wealthy, Thomas would have had no claim on federal dollars, and there would be no museum. But Glendora is not wealthy. And for this reason, stories about Kimbell, the gin, and the bridge continue to circulate, supported by nothing but the poverty of the town.

In 2008, this site was one of four Glendora sites added to the Tallahatchie Civil Rights Driving Tour created by the Emmett Till Memorial Commission.

Images