Mound Bayou

The activists and journalists who stayed in Mound Bayou were the only ones telling the true story of Till's murder. No one believed them

Although Mound Bayou is 42 miles away from Sumner, it played an essential role in the Emmett Till trial. The town provided protection for witnesses, a home base for the black press, and a refuge for Till’s mother Mamie Till-Bradley. Without Mound Bayou, we might still not know what happened to Emmett Till.

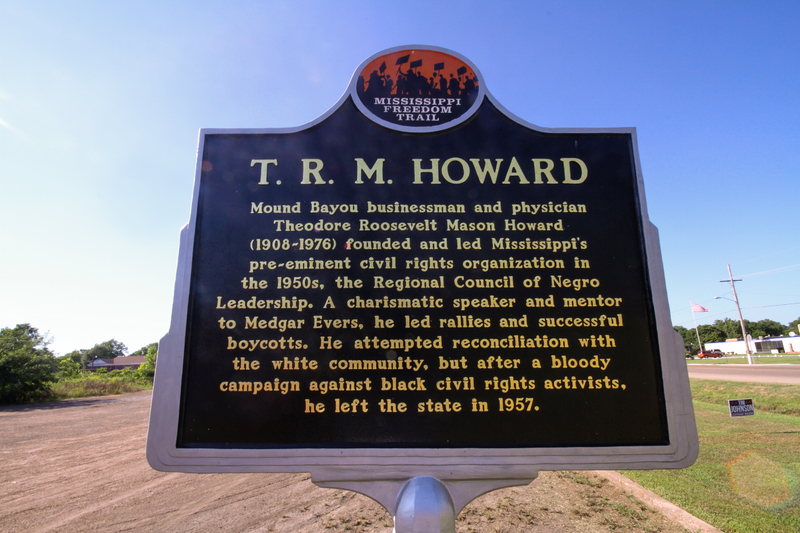

Mound Bayou was home to the legendary Mississippi activist Dr. Theodore Roosevelt Mason (T.R.M.) Howard. Although he is generally remembered for his 1951 founding of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership, Howard’s civil rights credentials were vast. He organized a non-violent movement in the Mississippi Delta four years before the Montgomery Bus Boycott (and three years before Emmett Till’s murder), he organized annual civil rights rallies, and he stoked Medgar Evers’ nascent activism by hiring him for his Magnolia Life Insurance Company.

His charismatic style meant that threats on his life were common. In the years before Till was murdered, Howard already had a $1,000 price tag on his life. He traveled with armed bodyguards, and his home featured twenty-four-hour-a-day armed protection. The sheer security of the Howard home explains why so many African Americans stayed with him when they came to Mississippi for the Till trial. Mound Bayou may have been 42 miles away from Sumner and the trial, but it offered unsurpassed safety. This is why Till’s mother Mamie Till-Bradley, Michigan Congressman Charles C. Diggs, and other African Americans used the Howard home as their base camp.

Beginning on the evening of Sunday, September 18, 1955, Howard’s home became far more than a base camp. Around midnight on the 18th, a young black plantation worker named Frank Young arrived at the Howard home claiming that he had direct evidence linking J. W. Milam, Roy Bryant, and four others to the murder. He also broke the then-shocking news that Till had been killed in Sunflower County. This was timely information. A widely-recognized liability of the prosecution’s case was their inability to locate the site of the murder. Just six days earlier, defense lawyer J. J. Breland had predicted an acquittal based, in part, on the inability of the prosecution to determine the murder site.

Young put these anxieties to rest. He told Howard that, at approximately 6 am on August 28, Till had been conveyed via a pickup truck crowded with four white people in the front and three African Americans in the back (including Till) to the seed barn on the Milam Plantation. Operated by J. W. Milam’s brother Leslie, the Milam Plantation is located about three miles west of Drew in Sunflower County. Young then told Howard that witnesses heard desperate screams emanating from the same barn; that they saw J. W. Milam emerge from the barn for a drink of water; that the screams gradually faded; and that a body was taken from the barn, covered with a tarpaulin, and placed in the back of a truck. He further assured Howard that this entire story could be vouchsafed by five Black witnesses: himself, Willie Reed, Add Reed, Walter Billingsley, and Amanda Bradley.

It is difficult to over-estimate the significance of Young’s account or its potential to challenge what people thought they knew about Till’s kidnapping and murder. It directly implicated far more people than J. W. Milam and Roy Bryant—who were the only defendants that week. It also implicated Leslie Milam, a fourth unknown white man, and two unknown Black men who were in the back of the truck with Till.

If Howard had any doubts about the veracity of Young’s story, he would have been reassured when, on the same night, Afro-American reporter James Hicks showed up directly from his experience at King’s Place in Glendora. Hicks’s story about Levi “Too Tight” Collins and Henry Lee Loggins fit perfectly with Frank Young’s tale. With the two stories combined, Howard now knew the identities of the two unknown Black men in the back of the truck.

The next evening (after the first day of the trial was complete), Howard called a strategy meeting at his home in Mound Bayou. Present at the meeting were NAACP officers Medgar Evers and Ruby Hurley and three influential members of the Black press: James Hicks, L. Alex Wilson (Tri-State Defender), and Simeon Booker (Jet). Although Hurley, Booker, and Hicks wanted to go public with the story immediately, Howard prevailed upon them to hold the story until the safety of the five witnesses could be assured. They agreed to contact the state’s lawyers through a trusted member of the white press, the Memphis Press-Scimitar’s Clark Porteous.

Porteous came immediately and met the group at Howard’s Magnolia Mutual Insurance Company. They made a plan: Porteous would invite District Attorney Gerald Chatham and his assistant Robert Smith to a second meeting at Howard’s home at 8 pm the following day. Medgar Evers and his NAACP colleagues would don cotton-picking clothes and go undercover as sharecroppers to bring the witnesses to the meeting. Once everyone was assembled, Howard would tell Young’s story, produce the five witnesses, and prevail upon the lawyers to stop the trial and move it to Sunflower County.

The meeting never happened. After Porteous conveyed the news to Chatham and Smith during Tuesday’s lunch recess, officials from Sunflower County headed to the Milam Plantation and inadvertently scared the witnesses. When the witnesses failed to show up for the meeting, the Black press and white legal establishment joined forces in what Simeon Booker later called “Mississippi’s first interracial manhunt.” By 3 am on Tuesday, September 20, the team of Hicks, Booker, Porteous, Featherstone, and Leflore County Sheriff George Smith had made contact with each of the five witnesses. Howard assured the witnesses they would be kept safe (Willie Reed moved in with Howard that night) and promised each of them jobs in Chicago in exchange for their testimony.

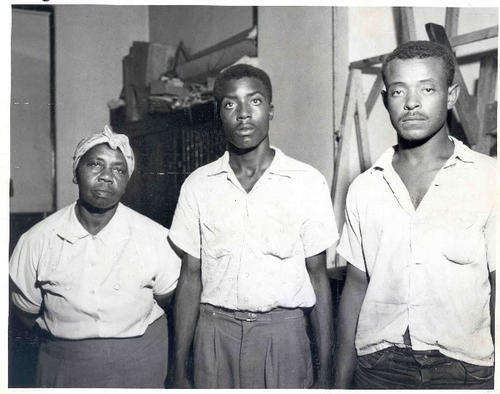

On Thursday, September 22, 1955, Willie Reed left the home of T. R. M. Howard and proceeded to Sumner, where he testified that Till was beaten on the Milam Plantation near Drew by J. W. Milam. It was a remarkable act of bravery. Although the jury chose not to believe him—dismissing his testimony as “just a good story”—the FBI has confirmed that Reed was one of the few people in the trial who was actually telling the truth.

After testifying, he returned briefly to the plantation. He then walked six miles to a pre-arranged meeting point, from whence he was taken one final time to the Howard home. From there he was taken to Memphis by Congressman Charles C. Diggs where, with only the clothes on his back and one extra pair of pants, he boarded a flight for Chicago. He never returned.

Images

Documents

| Name | Info | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Simeon Booker, "A Negro Reporter at the Till Trial." | pdf / 519.77 kB | Download |